Edward Hopper depicted a very bleak and lonely America. Paintings such as Nighthawk and Automat capture the paradox of loneliness in a community. But this painting, House by the Railroad, in 1925, captures what it is to be lonely in the early suburbs.

Notice the raised railroad tracks in the foreground that frames and supports the forlorn Victorian house. Is this the cause of the isolation? Is this the cure for the isolation? Are they in harmony? Or is one dramatically and radically opposed to the other? The residents of this house and houses similar to it presumably rely upon the train to travel to town for culture and entertainment, but Hopper’s other works might make us think that no meaningful human interaction awaits there either.

Still, as film directer Michael Mann commented, “There’s a solace to the loneliness. It’s a very emotional painting, and that is something that’s uniquely American. Transience is an American Experience in a way that it isn’t in other places.” Hopper’s Mansard mansion with its steeply sloped roof is a reference to the urban architecture of Paris, a city known for its fraternity. But, solitude is the way of the American. Ever since the Puritans landed in New England, our doctrine has not just been sola scriptura, but solo scriptura; that is, orthodox faith is not only determined solely by scripture, but it is determined solely by an individual’s interpretation of scripture.

Another early American painter, Grant Wood, captures the solitude of the American landscape. The rolling hills in this painting, New Road, are pastoral and bucolic, and the colors simply simply proclaim the beauty of the American countryside. But the sign in the corner of the painting points away from the house at the street corner and toward the salon, 5 miles away. While Wood glories in the rural farmland, it is merely the backdrop for the lonely, barren road.

A slightly more populated Wood painting is The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. Again a lonely, disappearing road is the focus, and even though the scene is more urban, it is shockingly vacant; the people are no more than white night-gowned specks. Small distances in this small town are exaggerated by a dramatic aerial vantage, negative space between structures, and a deep, dark horizon. The painting is quaint; however, unlike the town nestled safely below the fortified ridge, small town innocence sits at the top of the cliff, about to be shoved down into the canyon of materialism, greed, efficiency, and all the rest that post-WWII suburbanism brought with it.

The term for and therefore idea of a suburb is not new. Henry C. Binford reports: “For centuries, the term denoted an undifferentiated zone outside the city limits…after the 1850s suburbs meant a collection of separate communities housing many city workers, linked to the city through commuting.” The industrialization of commuting—from walking and riding horses to riding trains and later cars—incited a change of landscape. The suburbs were at first a luxury of the rich. Only those who could afford properties both in and out of town could experience both city and country. But America is founded on the principles of liberty and justice for all.

Democratic and economic forces combine with the huge infrastructural change we all know about: Henry Ford’s Model T and Eisenhower’s National Defense Highway System. Easy motoring combined with the formidable sway of individualism and self-sufficiency drove most Americans out of the city and into the ‘burbs. However, the trip was given a helpful starting push from Levitt & Sons. Historian David Popenoe summarizes it well:

November 8, 1951, is a day to be remembered throughout America. It was a day the largest residential home builder in the world changed the life style of thousands of American citizens. It was the day that people of low and moderate income became a partner and sharer of the opportunities in the free enterprise system. It was the day a $100 deposit bought you a ranch type home, on a minimum lot of 70’ x 100’ in a proposed planned, fully landscaped open spaced, garden community with paved roads and all utilities. It was the day, which five years later, would produce 17,311 homes and involve a population of over 67,000 residents. It was the day Levitt & Sons opened their sales office at the intersection of Route 13 and Levittown Parkway (112).

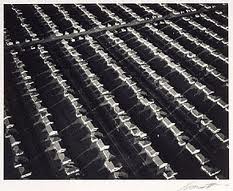

Levittown looked and functioned as the prototype for the suburbs that we are familiar with today: endless rows of houses, mismatched lawn shrubbery, household appliances, naked children in the front yard, and of course that mass manufactured, prefabricated aesthetic we all so love and hate.

But we have heard the historians critiques of the suburbs far too often. We know the white-flight, cheap housing, and government subsidized highway narrative. We all resonate with social commentator James Howard Kunstler when he describes the suburbs as, the “Jive plastic commuter tract home wastelands, the potemkin village shopping plazas with their vast parking lagoons, the Lego-block hotel complexes, the ‘gourmet mansardic’ junk food joints, the Orwellian office ‘parks’ featuring buildings sheathed in the same reflective glass as the sunglasses worn by the chain-gang guard…” (101). This is an old critique by now. So let us instead ask what the artists see in the suburbs.

One of the first artists to photograph early West Coast suburbs was William Garnett. Garnett’s photos strongly resemble the abstract expressionists’ paintings. The emphasis is taken away from the actually subject matter, though that is still intelligible, but it is instead transferred to the play of shapes and values. Stare at his photographs long enough and the content simply disappears and the image becomes a series of dichromatic lines. It prompts the ab-ex painters’ primary question: How does this art make you feel?

Another famous photographer from this time is Edward Ruscha. Ruscha brings us back to the dreaded and revered isolationism. In the early 90s, he published a series of several astounding aerials capturing empty parking lots. The first is a vacant drive-in movie theater in Central LA, the next a vacant Dodgers Stadium. As with Garnett’s aerials, the purity and symmetry of the shapes invite us in. But there is simultaneously something so repellent about an empty lot; perhaps we squirm at the thought of so much land gone to waste, perhaps we mourn a bye-gone era, or perhaps deep inside we truly fear being left alone in an empty lot.

A third photographer, Garry Winogrand, captured a different side of the American story. While Garnett and Ruscha viewed the suburbs with the abstractionists’ eyes and tried to provoke a thoughtful sensation in their viewers, Winogrand revealed the meaningless of the American project. He is quoted in Honour and Fleming’s comprehensive history, The Visual Arts:

I look at pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and what we feel and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I read newspapers, the columnists, some books, I look at the magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life. I cannot accept my conclusions, and so I must continue this photographic investigation further and deeper. This is my project.

Where have we seen this deep, unsettling yearning for meaning before? Photographs like Staten Island Ferry, New York City, NY, capture the aimlessness of our culture. People are looking everywhere for meaning: down at the sea, up in the sky, into each others eyes, off towards the city, and off towards Lady Liberty. But no one looks where towards where the ferry is headed. The girl in the foreground even looks defiantly backwards.

One way artists fill this void of meaninglessness is to fill their life with symbols. One of my favorite images of this time comes from a Smithsonian Exhibition on suburbia and its symbolism.

The exhibition, put together by famed architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, was ironically called “Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City.” Venturi has this to say about symbols: “The idea of symbolism is most important. That’s what we, as well as a few others, brought back into architecture. It had been expressly thrown out by the modernists, although it was readmitted on the sly in the symbolic industrial vocabulary they employed” (54). The exhibition mockingly calls attention to the haphazard amalgamation of historic styles that have been carelessly thrown together by architects. The architects assembled samplings from each style, but it was the owners duty to mentally put these together and come up with some sort of meaning. But, as Winogrand laments, how can anyone find meaning in this?

The built environment we inhabit today is primarily the vision of Le Corbusier. His concern, and the concern of the Modernist, is in solving humanities problems:

“A desperately backward concept of architecture, and their diplomas, are imposed officially by governments on a public opinion occupied until now with other concerns than verifying current credos…Ah, but excuse me, the people are not housed! for with such an architectural dogma and such practices, it is impossible to build houses at prices compatible with a country’s economy.”

To Corbu, the world’s great injustice is inequality, and he sought to remedy this his entire life.

But photographers like Winogrand and architects like Venturi deny that humans can do any such thing. Humans will never be truly equal, at least they will not be made so by any human effort. Vin Scully calls the modernist vision “anti-monumental” and “urbanistically destructive.” But the curious thing is, while we still inhabit this drab Corbusian world, we have all embarked on Winogrand’s quest to provide it with monuments of the true good and beautiful, thereby infusing it with meaning and riding ourselves forever of our loneliness.